Tell Them About the Dream: A Letter to Kansas City from 18th & Vine

Kansas City,

I’m writing this not as a politician, not as an academic, and not as someone looking in from the outside. I’m writing as a musician, a business owner, and a builder who made a deliberate decision to give my life’s work to this city’s cultural core.

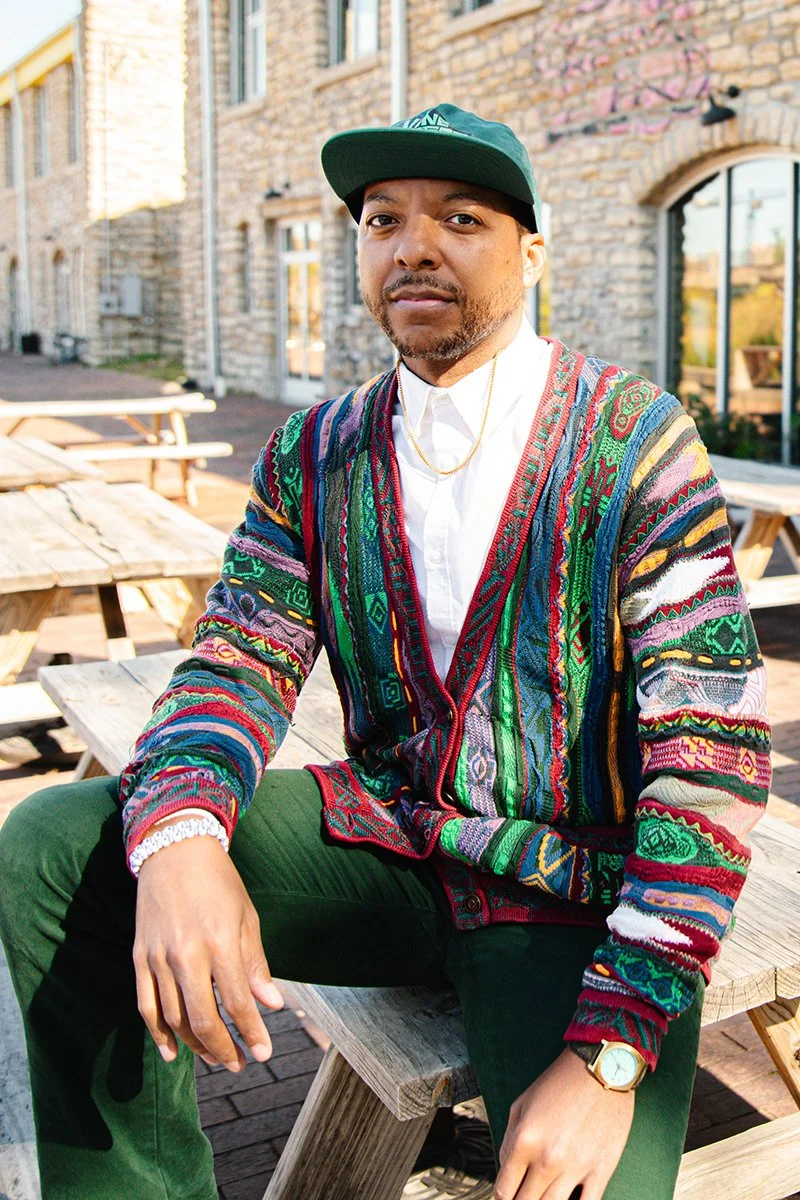

Photography by Laura Morsman

I’m Kemet Coleman. My partners and I founded Vine Street Brewing Company in an old stone public works building from the 1850s that had sat vacant for nearly 40 years. I chose to build at 18th & Vine not because it was easy, profitable, or obvious, but because it felt like the most honest place to stand if I wanted to understand Kansas City for what it truly is and what it could become.

That perspective matters right now.

The recent announcement surrounding the Chiefs didn’t just move a football team. It reopened something deeper. A wound this region has carried quietly for decades. A border war we joke about, normalize, and downplay until moments like this force us to confront it head-on.

This isn’t really about football.

It’s about identity.

Kansas City is in the middle of an identity crisis, and it’s arriving at the exact moment when clarity matters most.

When I was growing up here, Kansas City didn’t have an identity crisis. We had an inferiority complex. We were proud, but hesitant to say so out loud. Talented, but always measuring ourselves against Chicago, St. Louis, or the coasts. Somewhere along the way, that shifted. Attention arrived. Success followed. Now, on the eve of 2026, the problem isn’t that we think too little of ourselves. It’s that we haven’t agreed on who we actually are. An inferiority complex asks, “Are we good enough?” An identity crisis asks, “What do we stand for?” That’s a much more urgent question.

For too long, we’ve tied our sense of self to things that can be relocated, renegotiated, or rebranded. Teams. Developments. Rankings. Symbols that feel permanent until they aren’t. When civic pride fractures the moment something crosses a state line, it tells us something uncomfortable: we’ve outsourced who we are.

Kansas City does not lack talent.

Kansas City does not lack history.

Kansas City does not lack potential.

What we lack is alignment around our center of gravity.

To understand how we got here, we have to be honest. This metro was shaped by the automobile, federal housing policy, redlining, white flight, and development patterns that rewarded sprawl over density and power over proximity. Kansas grew through highways and expansion. Missouri responded through annexation to protect a shrinking tax base. Black families were pushed east. Investment followed privilege. Farm towns and rail stops became rival cities competing for the same future. Our Division I school is UMKC, yet civic gravity orbits KU, MU and K-State. These truths didn’t happen by accident.

Just to be clear, this history isn’t about blame.

It’s about truth.

Avoiding it hasn’t healed us. Pretending rivalry equals identity hasn’t unified us. And celebrating growth without asking what it’s anchored to has left us fragmented.

But history does not have to trap us.

The World Cup is coming to Kansas City soon. Not as a novelty. Not as a weekend event. But as a global moment of attention. The world won’t ask us which side of the state line our stadiums sit on. They’ll ask us who we are.

Atlanta once faced a similar moment. Before the Olympics, it was ambitious but undefined. That moment forced clarity. Atlanta didn’t just invest in venues. It invested in culture as infrastructure. Music. Film. Black excellence. Ownership. Creative industry. Atlanta didn’t simply host the world. It USED the Olympics to introduce itself to the world.

Kansas City now stands at that same threshold.

And this is where I feel compelled to speak plainly.

Kansas City feels like it’s standing at the podium right now. Measured. Prepared. Negotiating. Trying to say the right thing in a moment of deep division. I think about Martin Luther King Jr., steadying himself under the weight of history as he looked out over tens of thousands on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and toward what would become his most defining moment. And I hear Mahalia Jackson calling out from behind him with truth and urgency in the middle of his speech: “Tell them about the dream, Martin.”

So Kansas City, hear me clearly when I say this:

Let’s tell them about the dream.

Not because we’re lost, but because we already have it. We’ve lived it. We’ve shaped it. We’ve shared it with the world through music, culture, creativity, and resilience. The danger in this moment isn’t that we don’t know who we are. It’s that we forget to lead with it. And when this city remembers its dream, it stops arguing over borders and starts moving together toward its future.

Music has always been that mirror for Kansas City. Not as entertainment. Not as a weekend activity. Not as something we roll out for special occasions. But as identity.

Jazz gave Kansas City international relevance before we had a skyline worth photographing. It taught us how to collaborate, how to improvise, how to move together. That spirit didn’t disappear. It evolved. Hip-hop, gospel, soul, electronic, classical, experimental forms all carry the same DNA forward.

Music is not fragile.

Music is functional.

Music is infrastructure.

Live music is the smallest expression of that ecosystem. The real opportunity lives in film, education, technology, tourism, entrepreneurship, workforce development, ownership, and export. Treating music like something to preserve but not build with is why we’ve stalled.

In January 2025, I wrote A Musician’s Plea because I saw how often we treat music like beautiful, vintage wallpaper. Admired. Historic. Never structural. That plea still stands. If anything, this moment makes it more urgent. Kansas City cannot be the City of Fountains alone. We must become the City of Music, not metaphorically, but operationally.

If Kansas City is serious about identity, then 18th & Vine must move from symbolic to operational.

This district is not a museum. It is not nostalgia. It is not a branding exercise. It is the birthplace of Negro Leagues baseball, Kansas City jazz, Kansas City barbecue, and therefore a significant chunk of Kansas City culture itself. There is no other place in this city that can honestly carry that weight.

And yet, despite its global significance, it remains burdened by vacancy and disinvestment.

That contradiction is on us.

Nearly half a billion dollars of public and private momentum is already converging here. The 18th Street Pedestrian Mall. Parade Park. Structured parking. Museum expansion. Streetscape improvements. Add in the potential for federal dollars tied to cultural preservation, equitable development, and place-based revitalization, and the opportunity becomes undeniable. Smart cities don’t scatter momentum. They stack it.

Less than half a mile from where I’m standing is where the Negro Leagues were born. Not as nostalgia, but as innovation, ownership, and infrastructure. Baseball’s most powerful cultural chapter lives here. That history isn’t ornamental. It’s instructive.

Which brings us to a moment of responsibility (and I think you see where I might be going with this).

The Chiefs have, intentionally or not, created a moment of regional reckoning. Pain has a way of clarifying things. And in that clarity, the path forward becomes obvious. The Royals don’t need to look outward. They need to come home.

Home to 18th & Vine.

Poetically and quite ironically, Municipal Stadium, the former home of the Chiefs, once stood blocks from here.

As the founder of Missouri’s first Black-owned brewery, rooted in a building that sat vacant for forty years in the heart of this district, I understand what it means to bridge past and future in a way that’s real. Our presence here isn’t symbolic. It’s operational. Small but mighty. It’s proof that legacy and innovation can coexist and move a city forward together.

The city deserves for the Royals to be here. Not adjacent to culture, not borrowing it, but investing directly in it. To anchor themselves in the very neighborhood that gave Kansas City its national and international identity in the first place. To build forward from the most honest foundation this city has.

That wouldn’t be nostalgia.

That would be coming home.

That would be leadership.

Music doesn’t recognize state lines. Jazz didn’t. Hip hop doesn’t. The future won’t either. Music gives us a shared mirror. A way to see ourselves clearly, without rivalry, without fear, without distraction.

Kansas City does not need to win a border war.

Kansas City needs to remember who it is.

The World Cup will arrive whether we are ready or not. The only question is whether we will use this moment to clarify our identity or let it pass like so many others.

I believe this city is capable of more than we’ve allowed ourselves to imagine. But belief only matters if it turns into action.

Let’s tell them about the dream, together.

Kemet Coleman

Kansas City Native, Musician, Brewery Owner, Urbanist and Kansas City Advocate